Listed vs unlisted infrastructure through the lens of UK water utilities

The UK represents some of the largest opportunities for infrastructure investors irrespective of their ownership structures. This economy provides a vast array of assets, many widely held but largely homogenous. They're not differentiated by physical characteristics or regulation. Rather it's the achieved returns from that regulation that set them apart – an extension of quality management and constructive regulatory relations.

We believe it is these latter characteristics that drive a long-term differentiation on returns and valuation. For the rational investor, we suggest listed should be considered equally and alongside unlisted when considering an allocation to infrastructure. Here we show through the lens of UK water utilities why this is so.

UK water utilities – listed companies with a strong track record of outperformance

The UK water and sewerage companies are all regulated by the Water Services Regulation Authority, or OFWAT. Each year OFWAT publishes the financial performance of all water companies in the UK, whether listed or unlisted.

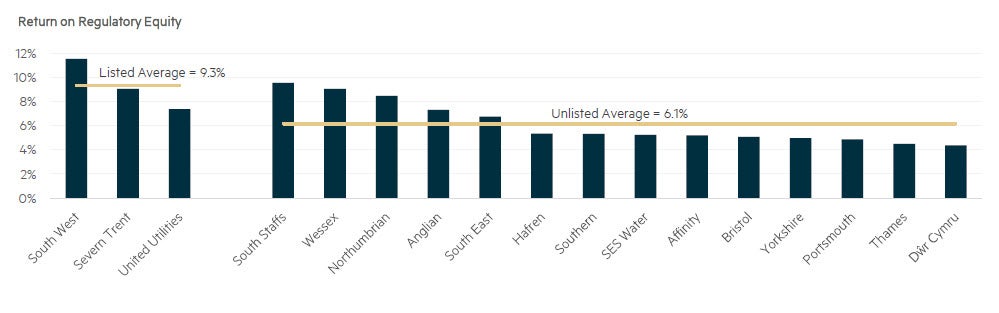

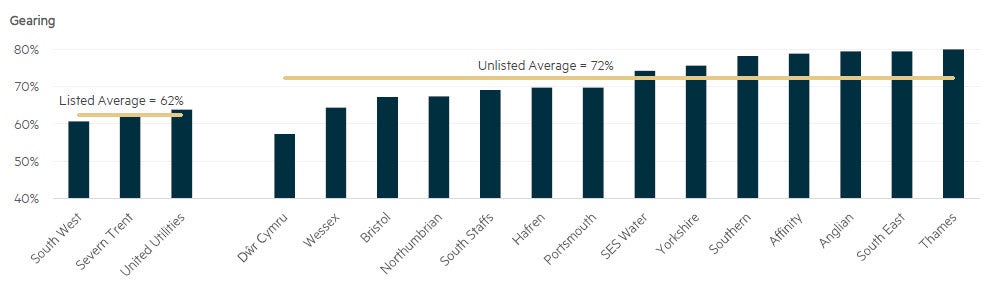

Listed water utilities in the UK have demonstrated superior operational performance and returns to equity compared to their unlisted counterparts. For every pound sterling invested in water assets over the 2015-19 period, the three water companies owned in the listed market generated an additional 3.2% return on their regulatory equity despite lower levels of debt (see Figure 1). The gearing levels in Figure 2 only include the debt inside the regulatory ring-fence and exclude the additional holding company debt typical for many of the unlisted companies. The three listed water companies were also fast-tracked for a price review in 2019, which allowed the companies to receive their draft determinations earlier than their unlisted peers.

The management of these listed companies operates and invests at lower risk to shareholders, with average gearing materially lower at 62.4% and in line with OFWAT assumptions, compared with those water companies owned by unlisted infrastructure investors at 72.4%. In other words, despite using more debt, the average unlisted water utility has not been able to boost its returns to equity. This is interesting because regulated companies, especially the UK water companies, are somewhat protected from the impact of higher interest rates as their allowed cost of equity (and debt) moves between regulatory resets. For example, every five years, the regulator resets the cost of debt and equity components of the allowed return on regulatory capital value (RCV) to account for prevailing debt and equity conditions. Although unlisted investments with debt levels materially higher than the regulator’s assumptions (62.5% gearing)(1) are currently benefiting from historically low rates, it must be highlighted that increased debt costs at the time of future refinancing creates a risk that it cannot be recovered. It is also worth acknowledging that historically the unlisted water utilities have paid less tax due to higher gearing and offshore structuring, attracting considerable regulatory and political scrutiny. Subsequent to this, OFWAT has sought to tighten the tax rules on such companies, which we consider to be detrimental.

Figure 1: Financial performance of UK water utilities from 2015–2019

Figure 2: Financial position of UK water utilities from 2015–2019

Source: OFWAT. Notes: Return on Regulatory Equity (RoRE) is the return to shareholders as a proportion of the equity component of Regulatory Capital Value (RCV). Gearing is measured as Net Debt to RCV. All values are 5-year averages from 2015-2019 (March year-end). Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Green credentials and compounding value creation

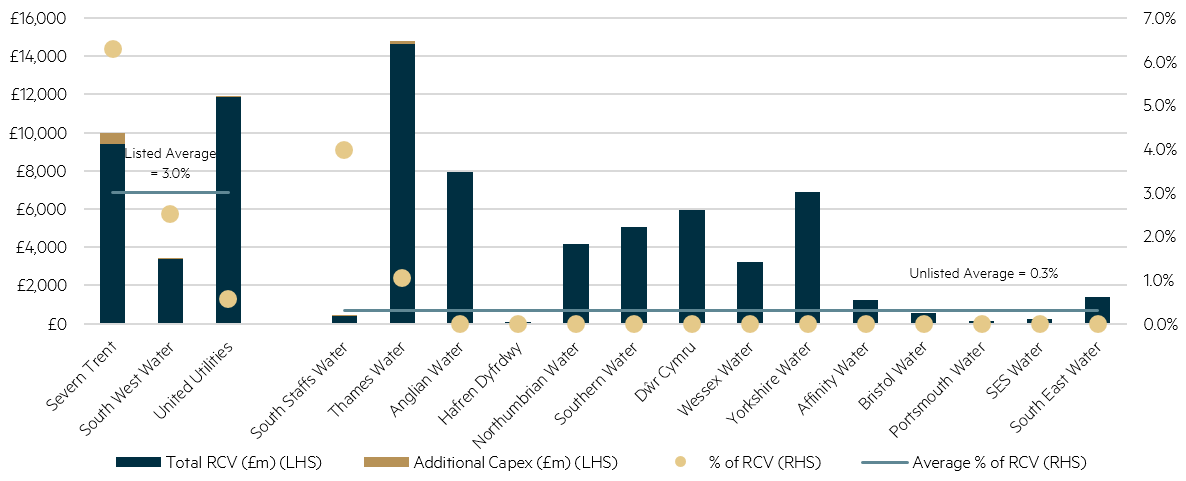

In July 2020, OFWAT invited water companies to play their part in the green economic recovery from COVID-19 to top up their five-year capital expenditure packages. In May 2021, OFWAT released its draft decisions on proposals received,(2) resulting in a significant step-change in regulated growth capex for a select few companies including the three UK-listed water utilities, Severn Trent, United Utilities and South West Water (Pennon).

It is remarkable to see the strong skew of support by OFWAT for incremental capex by companies owned in the listed markets compared with those that are unlisted. Three of the five companies with approved draft proposals are in listed markets and secured the lion’s share of new spend (see Figure 3). We believe this is the result of a combination of good government relations, strong performance on key objectives and a constructive rather than combative approach with the regulator. It is not surprising to us that these three listed companies were ‘fast-tracked’ in their most recent five-year regulatory determination, receiving some of the strongest regulatory support for additional green capex in the process.

There are currently four unlisted UK water companies appealing the most recent five-year regulatory decision to the Competition Market Authority (CMA). All of these companies appealing to the CMA appear to have missed the opportunity to secure any incremental growth capex as part of the green economic recovery process, highlighting a compounding impact of poor performance coupled with poor regulatory relations.

At the opposite end of the spectrum is the very public and constructive dialogue being seen between company and regulator in listed markets. For example, Liv Garfield, CEO of Severn Trent – the recipient company of the largest green economic recovery spend – noted the following on the company’s half-year earnings call in November 2020.

“There is a good government conversation right now about green recovery. And I think that’s about companies that have got strong operational performance, have proven that they’re ahead on their capital spend, are companies that are environmentally strong. Could they do more over the next few years on different activity areas and actually help the UK be a greener society at the end of it? We are having some good conversations around that with government, with Defra, with OFWAT. And I think we’ll know more in the next few months about that.”(3)

The timeline is interesting and indicative of this working relationship – the above comment on the green recovery plan was made almost two months before the company lodged their proposal with the regulator and almost six months before the regulator’s draft decision was published.

The three listed companies have been able to demonstrate how they would invest an extra £709m,(4) or 82% of the total amount awarded, for accelerating further environmental improvements, building flood resistant communities, repairing and replacing pipes and decarbonising water services. The silence from the majority of other companies in the sector is notable. OFWAT’s green push within the sector raises the environmental profiles of these companies, which are already sector-leading at a global level.

As part of their proposals, the companies needed to provide assurances around (1) their existing PR19 investment programs and performance commitments being on track, (2) their ability to deliver additional schemes without putting their PR195 investment programs or financial resilience at risk and (3) managing any affordability pressures for customers. For all of the unlisted-owned water companies currently battling OFWAT in the CMA and a select few others, we believe assurances on (1) and (2) are more difficult to address.

Figure 3: UK water companies’ total RCV and additional proposed allowances for green investment projects under OFWAT’s draft decisions

Source: OFWAT, 2021. Note: Company RCVs as at 31 March 2021. Additional capex amounts from OFWAT’s Draft Decision have been converted from 2017–18 to 2021 prices using OFWAT’s CPIH Financial Year Average Indexation.

We think the recent Green Recovery program is an excellent example of the strong management and governance in the UK listed water sector. We believe the awarded projects will improve RCV growth and prove to be accretive to these companies’ valuations. Severn Trent, the largest beneficiary, is now expecting over 10% real RCV growth over the current five-year AMP compared to their base real RCV growth of 3.8% at the time of their final determination, which is also high for the water sector.

1 OFWAT had set a notional capital structure with notional gearing of 62.5% Net Debt to RCV for AMP6 (2015–2020), being the period corresponding to Figures 1 and 2.

2 Source: www.ofwat.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Green-economic-recovery-draft-decisions.pdf

3 26 November 2020.

4 All figures from OFWAT’s Draft Decision are in 2017/18 Consumer Prices Index Including Owner Occupiers’ Housing Costs (CPIH) prices.

5 Price Review 2019 – for regulatory period 2020–2025.

Disclaimer

This paper was prepared by Maple-Brown Abbott Limited ABN 73 001 208 564, Australian Financial Service Licence No. 237296 (MBA). MBA is registered as an investment advisor with the United State Securities and Exchange Commission under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and works only with institutional investors in the United States. This paper does not constitute advice of any kind and should not be relied upon as such. This information is intended to be educational and to provide general information only, it does not have regard to an investor’s investment objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making any investment decision, you should seek independent investment, legal, tax, accounting or other professional advice as appropriate. This paper does not constitute an offer or solicitation by anyone in any jurisdiction.

The information in this presentation is not an advertisement and is not directed at any person in any jurisdiction where the publication or availability of the information is prohibited or restricted by law. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Any comments about investments are not a recommendation to buy, sell or hold. Any views expressed on individual investments, or any forecasts or estimates, are point in time views and may be based on certain assumptions and qualifications not set out in part or in full in this information. Information derived from sources is believed to be accurate, however such information has not been independently verified and may be subject to assumptions and qualifications compiled by the relevant source and this paper does not purport to provide a complete description of all or any such assumptions and qualifications. To the extent permitted by law, neither MBA, nor any of its related parties, directors or employees, make any representation or warranty as to the accuracy, completeness, reasonableness or reliability of the information contained herein, or accept liability or responsibility for any losses, whether direct, indirect or consequential, relating to, or arising from, the use or reliance on any part of this paper. This information is current as at 31 May 2021 and is subject to change at any time without notice.